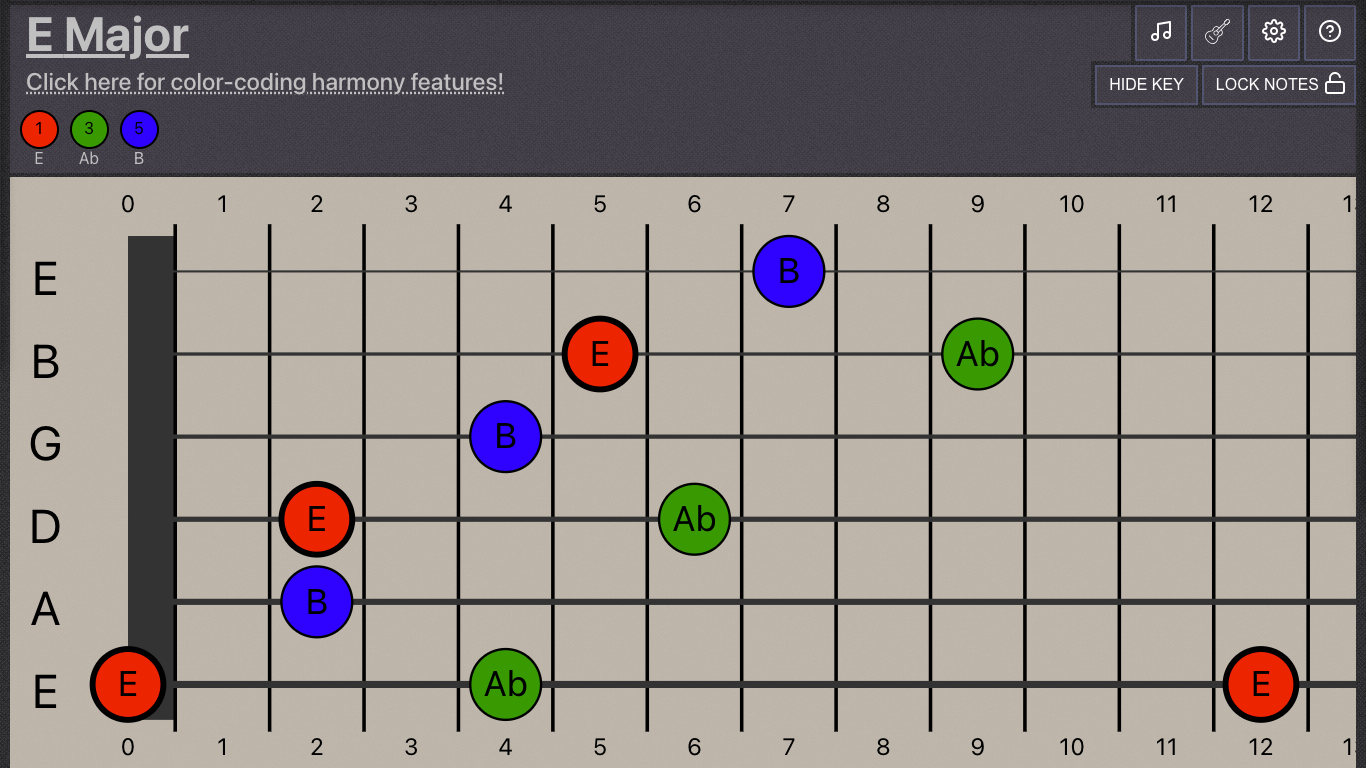

There has been a specific focus with using three-note chords in recent posts (here and here). None of the above posts have looked into arpeggiating three note-chords as sequential single notes and none of the examples contained two adjacent notes plucked on the same string. Playing three-note chords sequentially offers interesting creative opportunities. In this post we will examine arpeggiating three note chords using diagonal positions

Why Learn Arpeggios Sequentially?

While the previously explained exercises (here, here, here) are useful for developing picking motions, (which are their primary concern), and fretboard intuition, the exercises constrain melodic invention. Whereas sequentially playing through an arpeggio helps to survey potential notes in order of pitch. Furthermore, this helps to improvise melodies using the notes of a chord, developing an understanding of the chord-notes as entities within a harmonic and melodic context.

Exercises For Developing Three-Note Arpeggios

The following exercises are all going to use horizontal/diagonal patterns to move across the fretboard, see the post, here, for more information on this concept.

Basic Sequential Exercises

The first exercise is to simply play through each note of the arpeggio, one by one, in a steady rhythm, such as quarter-beats. Keeping things slow will allow more time for choosing effective fretting and picking technique. Everyone is different and hands, palms and fingers vary in size, there aren’t any one size fits all solutions. While it may not be a current consideration, as technique and stylistic idiosyncrasy develop these decisions may become more important.

The next exercise is very similar. Instead of playing each note once, each note is duplicated to create an eighth-note rhythmic pattern. A key difference to example one, is that the sheet music identifies a specific plucking hand pattern, represented by the little i’s and m’s by each note on the stave. These symbols are from the PIMA concept and explain that the index and middle fingers alternate.

Exercises Utilising Pattern And Groupings

The third exercise demonstrates implementing a pattern or grouping across the notes of an arpeggio. The example below shows grouping the notes into three and then moving back to the middle previous note. Move three in one direction, then back one, then move three again. The sheet music on the stave identifies this relationship visually. It’s not quite so clear from the tab.

The following example is an extension of the previous, the only different is that it extends to an even higher pitch, completing the third octave. I would suggest building confidence in the former before being too concerned about completing the next example.

No right hand plucking pattern was suggested for the previous two examples, but many different types of picking could utilised. By this stage, I hope it’s clear that with a bit of creativity exercises are easy to modify to satisfy particular ambitions or bespoke goals.

Playing Arpeggiating Three Note Chords Using Diagonal Positions: Final Thoughts

Playing single-note arpeggios almost as if a lead-melody is really great way to further fretboard intuition and fretting hand positioning. Everyone has different shaped-hands and ultimately this could consciously or even sub-consciously influence technique.

Anti-Fretting-Patterns

While creativity with slides, hammer-ons and pull-offs mean there are all kinds of possibilities and edge-cases. There are things that should definitely be avoided or encouraged. (Although in the case of younger people this is less of a concern.) For example, playing ‘in-position’, allocating adjacent fretting fingers to corresponding adjacent frets is a good way to maximise the economy of motion. Although somewhat contradictory, some would encourage the second fretting finger to stretch between two frets for faster traversal of three-note-per string-scales. Ultimately, there is no single true answer. Both of the described cases are widely implemented concepts.

Moving To Another Chord

There are plenty of ways to get creative with just a single triad, and that’s been the main focus of recent posts. However, playing the same three notes in lots of different ways gets boring quite quickly. Fortunately, changing chord is not actually a difficult thing to do. Using our knowledge of differentiation and variation it’s easy to apply these concepts to a harmonic form, such as a chord progression or harmonised scale.